The rise of digital media and the resulting changes in both the practice and business of news, the crisis of confidence in the media in many countries, and growing political pressures on independent journalism in others, animates an increasingly urgent conversation about the future of journalism.

The academic field of journalism studies often seems virtually absent from that conversation.

We might feel that we, like other scientific fields, have “epistemic authority” over our main object of analysis, the legitimate and recognized right to define, describe, and explain specific aspects of reality.

But few seems to care what we know, or find what we do relevant. As former ICA President Larry Gross said at ICA in 2017, we, like other media and communications researchers, may feel we have a lot to offer. But the debate is in practice often dominated by lawyers, economists, and consultants.

Similarly, with some notable exceptions, much of the discussion around what we study—journalism, its output, and the relations that constitute, define, and enable it in different contexts—is driven by practitioners, pundits, and scientists from other fields.

Journalism studies, on the other hand, seems largely absent.

Some of the factors accounting for our relative absence are surely external to our field, things over which we have little control.

But there are arguable also internal factors, factors we might address if we want to be part of the conversation about the future of journalism.[1]

One factor is not showing up.

Consider for example the International Journalism Festival, held every spring in Perugia in Italy. It can serve as a useful illustrative case because it represents a fantastic opportunity to engage with many different voices engaged in the conversation around the future of journalism. (There are many ways to engage, including writing for popular outlets, social media, and private conversations with journalists. But attending professional and industry events like IJF I think are an important example of engagement.)

The festival is free to attend, and draws thousands of people, including hundreds of speakers from news media, technology companies, and policymaking circles. It is genuinely international with participants from many different countries. It is proudly open and inclusive in providing a platform for many different voices from many different backgrounds—those interested simply propose a panel and the organizers work to accommodate all they can, and subsidize most of the speakers.

IJF is fantastically interesting, good fun, and, from an engagement point of view, a cheap, easy, and engaging way for academics to learn from journalists and others and share work with them.

However, it appears that not many academics do so.

Consider the 2018 festival, which hosted more than 500 speakers. Looking specifically at the 386 international speakers, and defining an academic speaker broadly as someone who list their main affiliation as a university and works at least in part with research, I could identify only 40 academics, 10%, amongst the speakers.[2]

Even more strikingly for a festival in (continental) Europe, a full 31 of these worked at UK (18) or US (13) universities. The third largest group by country of work? Canada (!) with 3, followed by Belgium, France, Germany, Serbia, Spain, and Turkey with one each. Leaving aside Italians and the UK, there were just 6 academics from the rest of Europe combined, about 1.5% of all festival speakers.

If we are serious about being part of the conversation about the future of journalism, we need to start showing up to events like this, and show up in numbers and in all our diversity.

I have no problem with the fact that 90% of the IJF speakers are non-academics. I enjoyed every single panel I went to and learned a ton, often especially from non-academics.

But I do think it is a shame and a missed opportunity for academics, both individually and institutionally, that so few of us show up for events like the IJF that provide such a perfect opportunity for learning from and sharing with practitioners, policymakers, and members of the public interested in what we do.

Some scholars have developed a normative idea of “reciprocal journalism”, based on the idea of mutually beneficial forms of exchange.

Perhaps we need an similar commitment from academics to “reciprocal research”, strengthening our own work while also giving back to the public, the people we study, and policy-making discussions?

Some scholars do already show up, judging by the 2018 numbers especially academics from the UK and the US. What drives this strong representation?

Some of it is surely the added visibility and reach that can come with working in English, and in the case of the US a large field of academics with international interests.

But remember, IJF is open to anyone who pitches a panel. (I have no reason to think the festival routinely rejects relevant proposals, but can’t really know from the outside – if anyone has had such experiences, please let me know.)

So part of the reason is likely that UK and US academics pitch more frequently than their counterparts elsewhere in Europe and beyond.

One possible explanation is the growing number of extra-departmental, inter-disciplinary centers committed to connecting research and practice that seems particularly prevalent in English-speaking universities. (This would include for example POLIS at the LSE in the UK and Agora at the University of Oregon in the US as well as us at the Reuters Institute in Oxford.)

Such centers account for only a tiny part of the overall number of academics researching journalism, but they are important because they operate differently from traditional departments where, I would posit, the informal norms and formal reward systems of our field often do not reward engagement, and often tend to reward inwards discussion and narrow specialization.

Centers, in contrast, can serve as what science and technology scholars call trading zones, spaces where the development of interactional expertise helps people with different practical experience, professional objectives, and forms of substantive expertise collaborate across their differences.

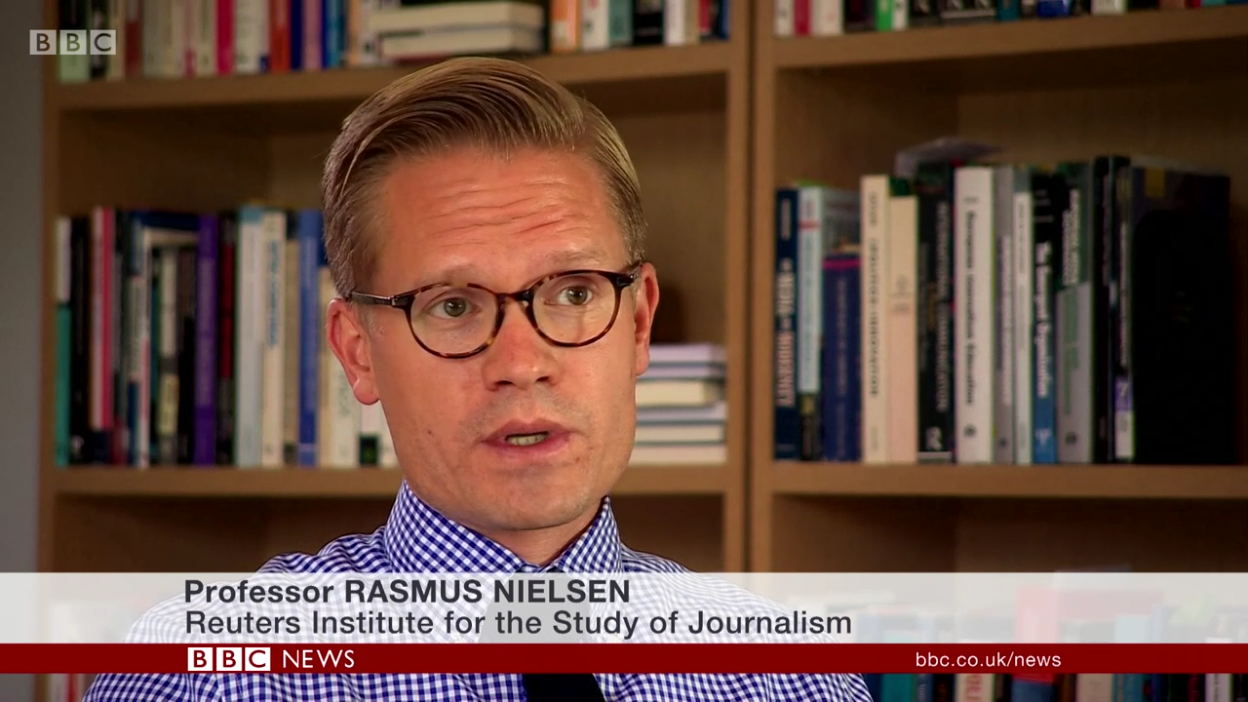

And indeed, if we break down the 40 academics who presented at the International Journalism Festival in 2018, by my count, 13 out of the 31 UK and US academics come from various extra-departmental, inter-disciplinary centers focused on connecting research and practice. 6 are associated with the Reuters Institute alone – more than the total number of academic IJF speakers from Belgium, France, Germany, Spain, and Turkey combined. (I am not familiar with all the academic institutions people work at, so I may have under-counted centers based in countries where I do not speak the language. When in doubt, I have assumed people are based in a department, not a center.)

Some may see this difference between departments and centers as a zero-sum trade-off or a division of labor. From this point of view, departments focus on basic science, centers do applied work and engagement. I think this is often misleading.

A different perspective and from my point of view more useful approach is the one developed by some sociologists of science, who have distinguished between what they call “Mode 1” (an older paradigm of scientific work, driven by academically exclusive, investigator-initiated, and discipline-based forms of knowledge production) and “Mode 2,” the kinds of context-driven, problem-focused, and interdisciplinary forms of knowledge production that are central to some of the most successful fields in science today, like computer science, engineering, and medicine.

From this perspective, all centers can benefit from doing some basic science, and all departments can benefit from more engagement.

I would suggest much of the work done in journalism studies today often aspires to the inwards-looking “Mode 1” model, whereas work done in extra-departmental interdisciplinary centers aspires to “Mode 2” forms of knowledge production in ways that tend to encourage engagement with an evolving set of both inside and outside partners and focus on contemporary issues.

The difference here is not between basic and applied research, or between intellectual substance and practical application, but in how questions are asked, why, how work is done, and how it is published.

At the Reuters Institute, for example, we combine self-published fast turn-around reports with peer-reviewed articles in top outlets like the Journal of Communication and New Media & Society.

Similarly, many other academics who spoke (and listened) at the International Journalism Festival combine a focus on scholarly work with a real commitment to engagement with practitioners, whether already established figures like Charlie Beckett and Regina Lawrence, people like Nikki Usher and Ruthie Palmer from my own generation, or PhD students like Lisa-Maria Neudert and Philip di Salvo. If we as a field are serious about engaging in the discussion, learning from and sharing with journalists, policymakers, and the public, we should recognize and celebrate those who do, especially early career researchers who are frankly taking a risk – one I think they should and will be rewarded for – when they take out time to attend things like this rather than trying to crank out yet another peer-reviewed journal article.

Both “Mode 1” and “Mode 2“forms of knowledge production have different strengths and weaknesses, but there is no doubt which one prioritize engagement the most, nor which of them privilege what former ERC President Helga Nowotny has called “social robustness”, the aim of producing “robust knowledge” that is relevant to and accepted by actors in the context of its application.

My own view is that “Mode 2” offers a very promising model of knowledge production for journalism studies if we wish to produce knowledge that is relevant and robust in addition to being distinct, valuable, and reliable.

From this perspective, more engagement would not be distraction for journalism studies, but a way of enriching our work, while also making a greater contribution to public debate, and perhaps to the public. I think this has great potential, for journalism studies as a field, and for the discussion around journalism, and hope many more academics will join.

At its best, journalism studies can be an important part of the conversation about the future of journalism.

But to do so, we need to start showing up, listening to and learning from those already engaged in the discussion, integrate such engagement in what we do and what we value as a field, and work hard to make sure that our work brings independent evidence and insight to the issues of the day.

As John F. Kennedy is supposed to have said, “Every accomplishment starts with the decision to try.” I suggest academics interested in engaging more with those most active in the discussion around the future of journalism, and learning from this conversation start by showing up in greater numbers.

Perhaps try it by coming to the IJF in Perugia next year? It’s April 3-7. Mark your calendar. I’ve marked mine. I hope to see you there.

Notes

[1] I’ve written about similar issues in the field of political communication research here.

[2] This is not a formal content analysis and done quickly on my own by looking through all speakers and categorizing them on the basis of their stated affiliation. The definition of “academic” means that Aron Pilhofer, who does not have a PhD but does important work at Temple University, is counted as an academic, while Guy Berger, who is an accomplished academic but works for UNESCO, does not (nor does Alan Rusbridger who at the University of Oxford, but as Principal of Lady Margaret Hall). I have coded people by the institutional affiliation they provide, not their country of origin.