Back in August, Meera Selva, Joy Jenkins and I — all from the Reuters Institute — started asking people for suggestions of what academic work on journalism/news/media it would be useful for journalists to read.

We wanted to create a list of reading suggestions for the incoming Reuters Institute Journalist Fellows, mid-career journalists from all over the world who spend between 3 and 9 months with us in Oxford working on a project of their own choosing

A stable version is on the institute website here, and a Google Document open to editing is here.

We also hoped this would be useful for journalists elsewhere thinking about the present and future of their profession, the institutions that sustain and constrain it, its social and political implications, and how it is changing.

I’ve often felt (and written about) that academic research on journalism is too disconnected and far removed from urgent, present conversations about the future of news, so it was great to be reminded that there are many in the academic community who care about how research can play a role in these discussions, and enthusiastically offered up suggestions.

We had hundreds of suggestions — and I’m sure we could have collected or come up with hundreds more — so what we have done to make it a bit more managable and easy to access is to create 17 topics with a few suggested readings, including one marked as a good place to start on that topic, and then collected the other suggestions at the back of the document.

The 17 topics, and suggested first readings, are

1. Some classic big ideas on journalism, media, and ideas in public life

* Lippmann, Walter. 1997. Public Opinion. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A: Transaction Publishers.

2. What is journalism and news?

* Deuze, M. (2005). What is journalism? Professional identity and ideology of journalists reconsidered. Journalism, 6(4), 442-464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905056815

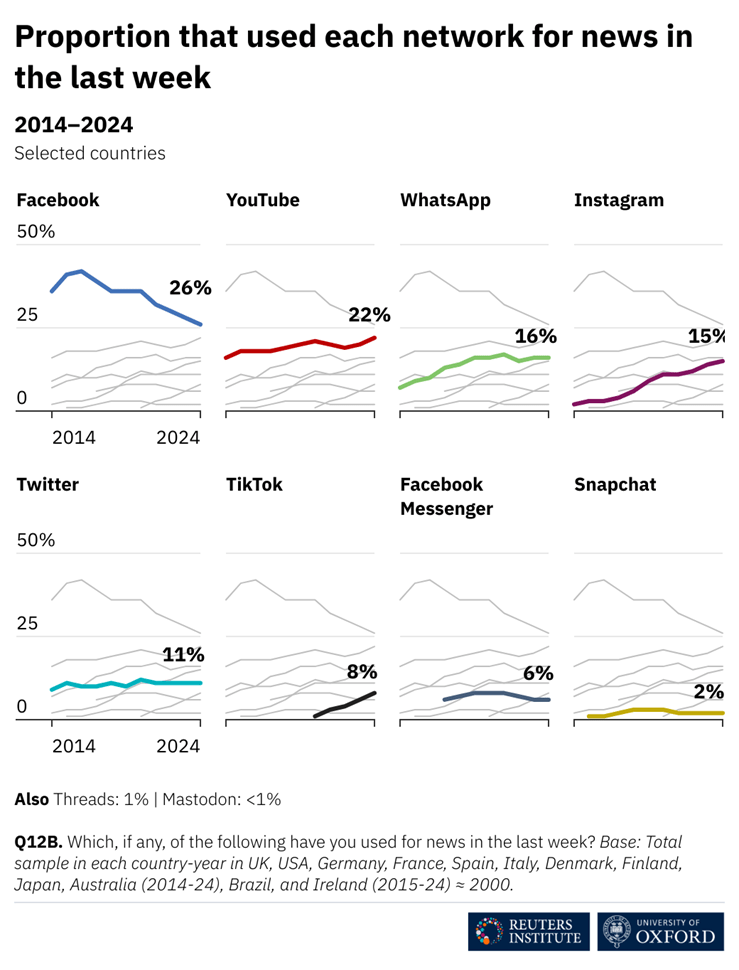

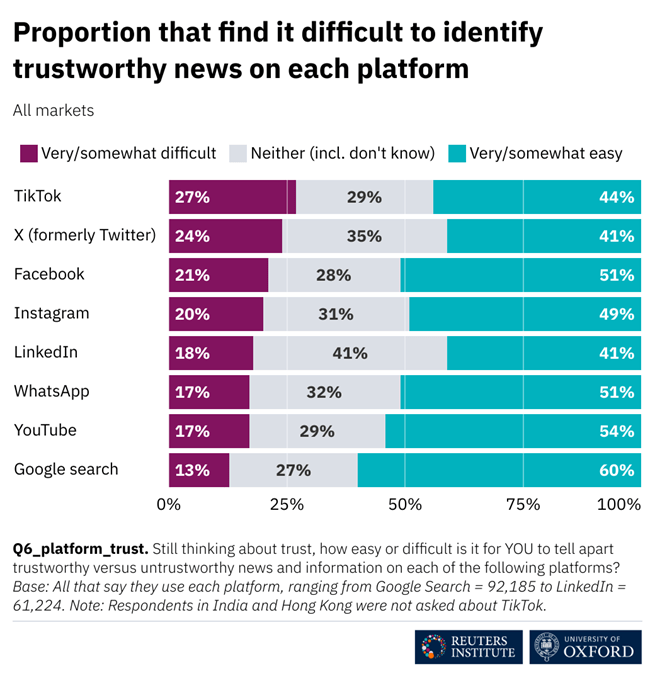

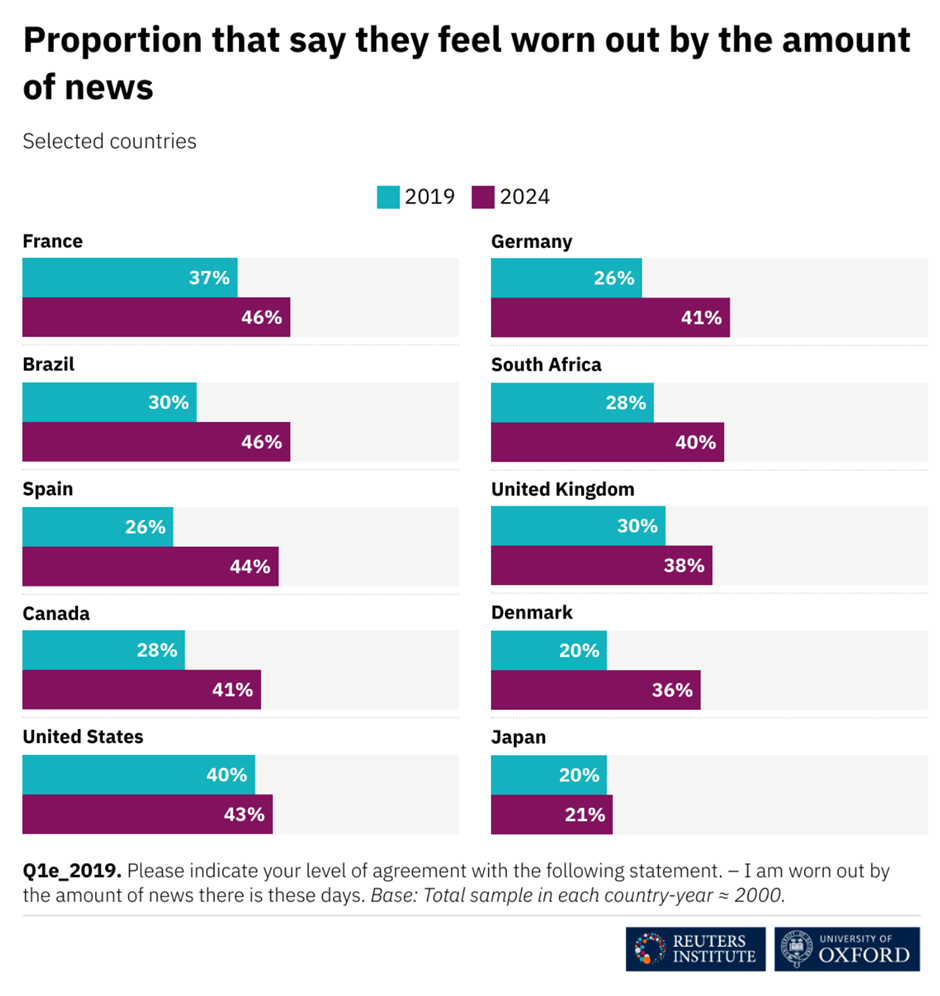

3. Audience behaviour

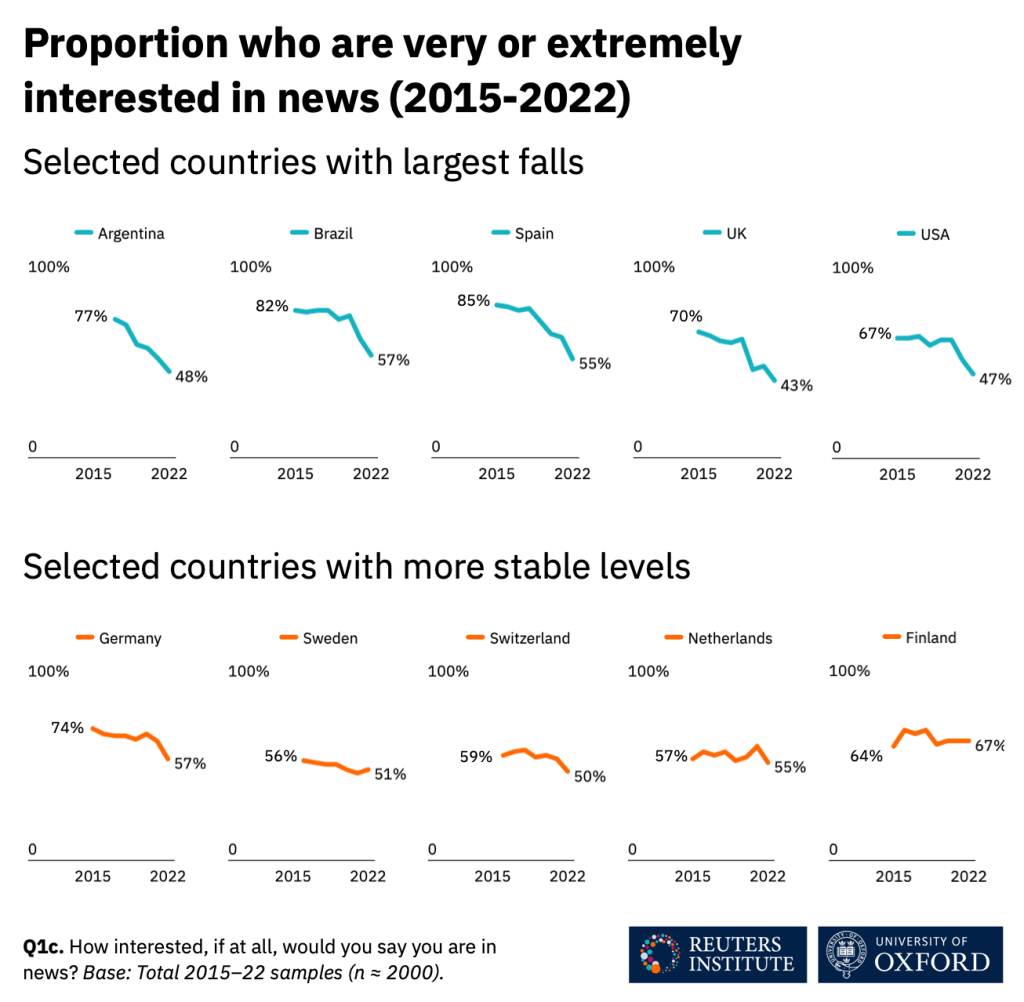

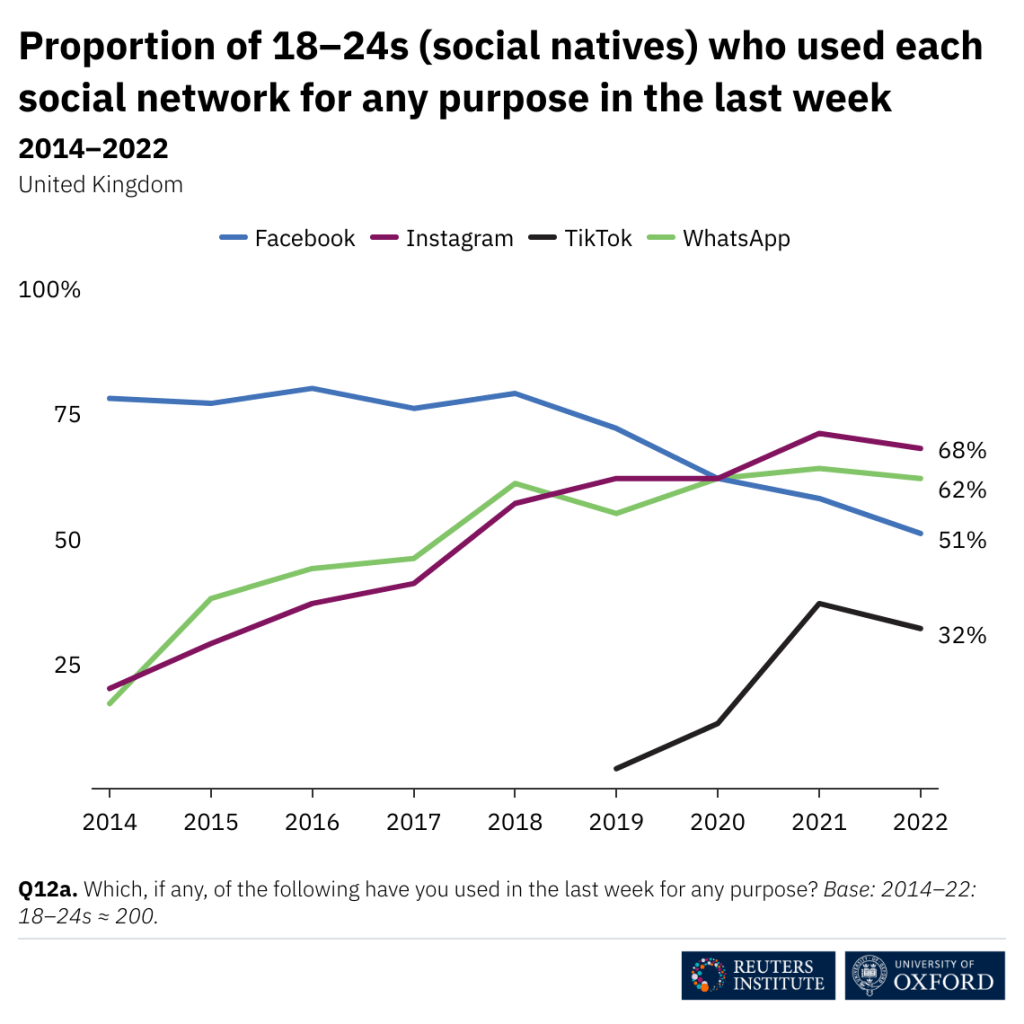

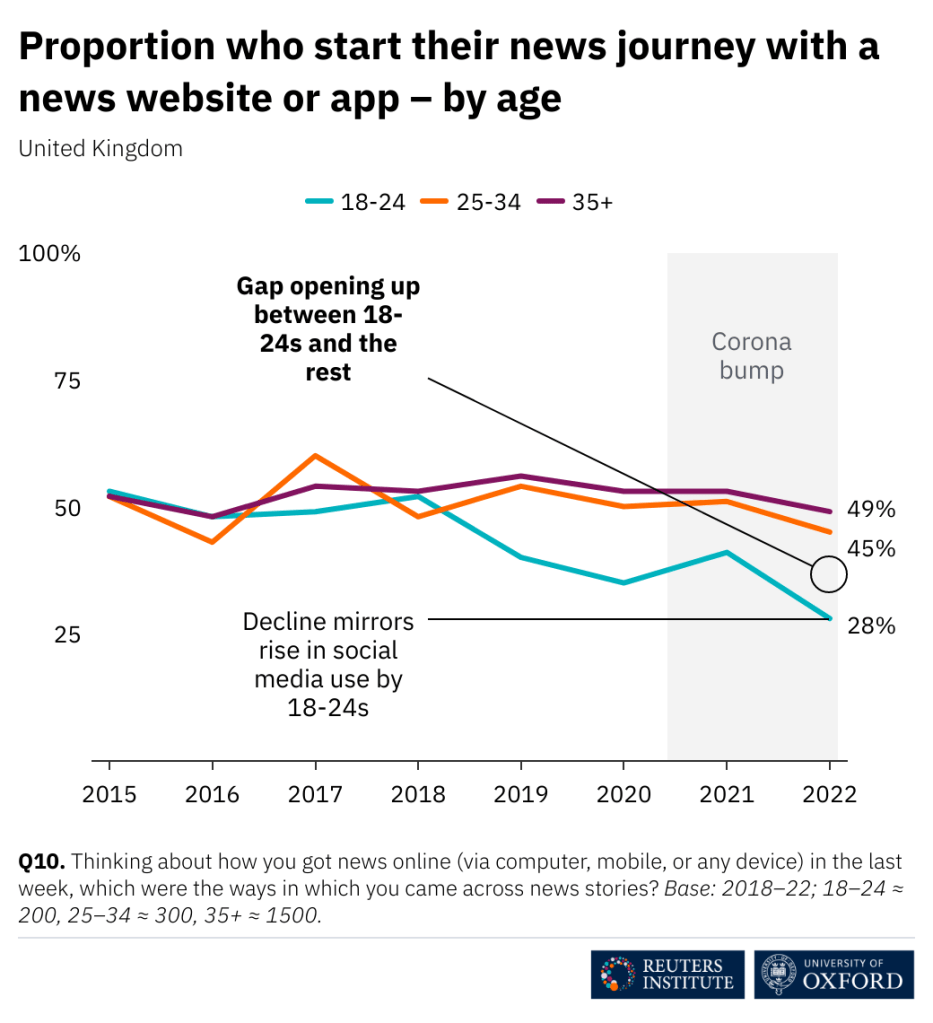

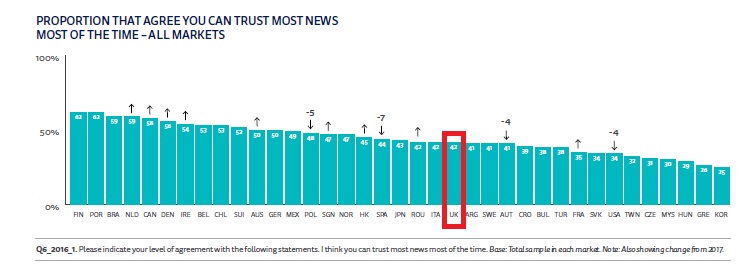

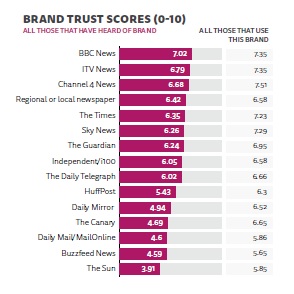

* Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018.” Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/.

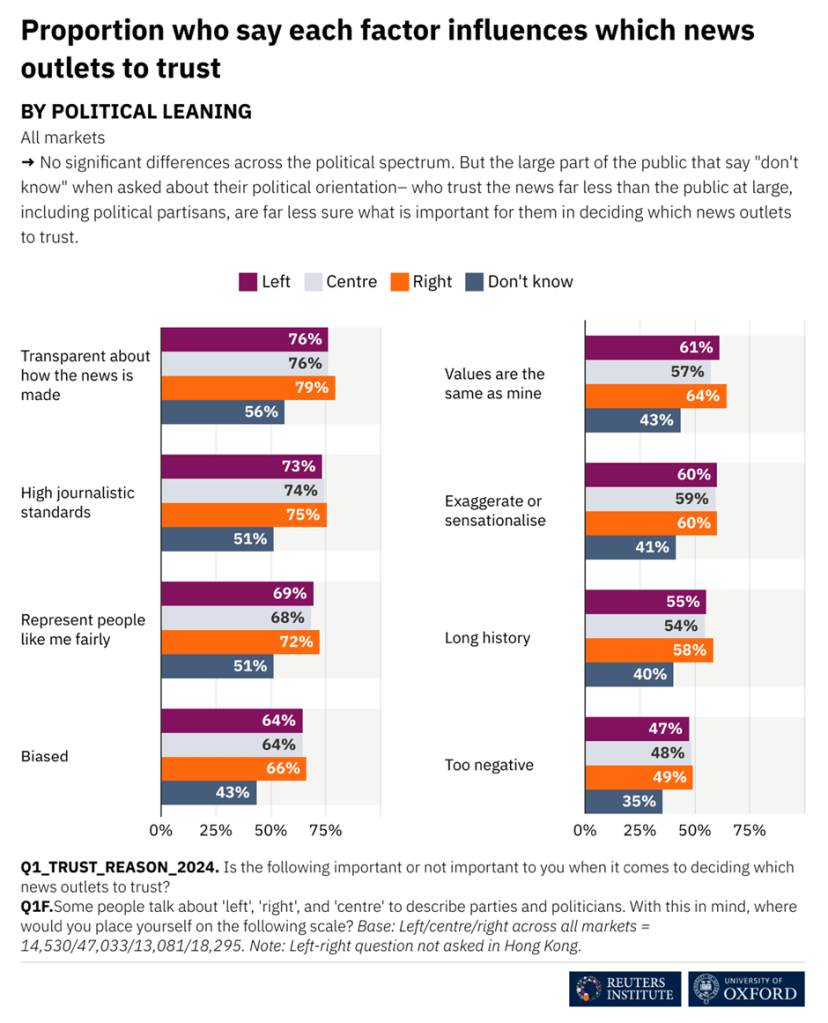

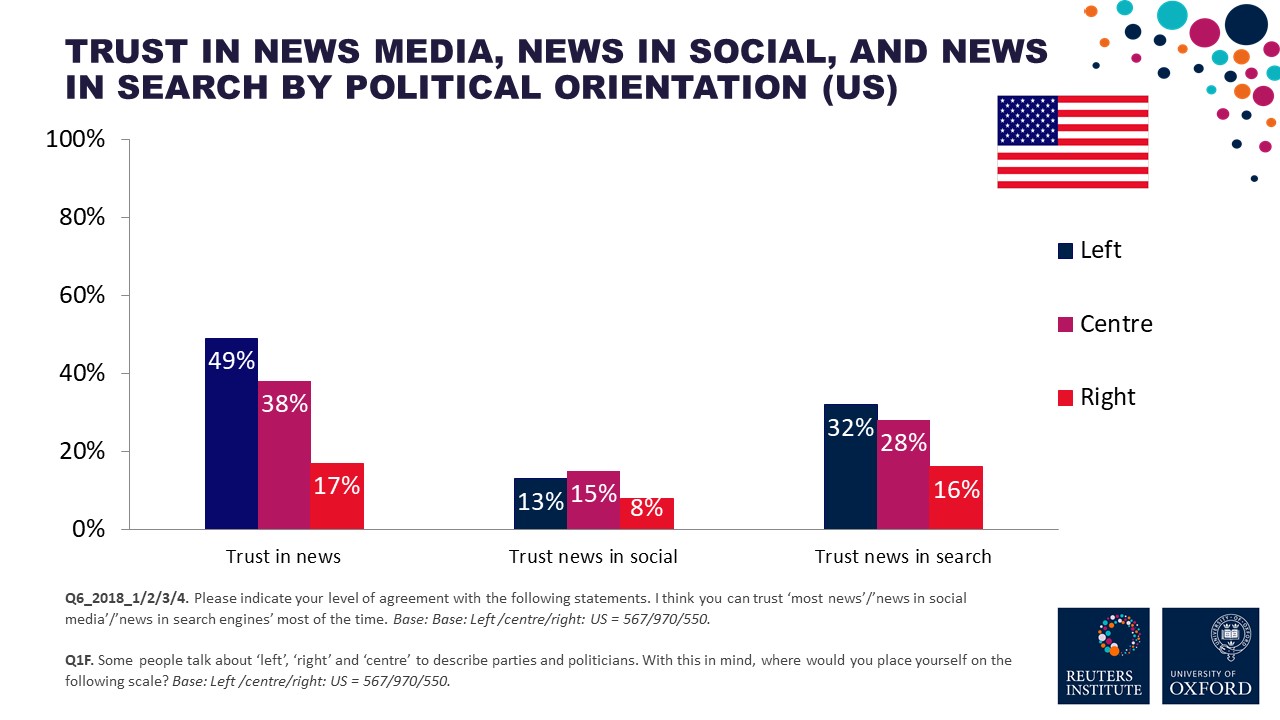

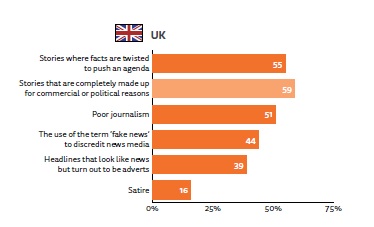

4. Trust and the news media

* O’Neill, Onora. 2002. A Question of Trust. Reith Lectures ; 2002. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Also available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2002/lectures.shtml)

5. Inequality and polarisation in news use

* Prior, Markus. 2005. “News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political Knowledge and Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 577–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00143.x.

6. Framing and media effects

* CommGap. 2012. “Media Effects”. World Bank Communication for Governance Accountability Program. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGOVACC/Resources/MediaEffectsweb.pdf (short overview).

7. Relations between reporters and officials

* Bennett, W. Lance. 1990. “Toward a Theory of Press-State Relations in the United States.” The Journal of Communication 40 (2): 103–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x.

8. News, race, and recognition

* Lamont, M. (2018). Addressing recognition gaps: Destigmatization and the reduction of inequality. American Sociological Review, 83(3), 419-444. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0003122418773775

9. Women and journalism

* Franks, Suzanne. 2013. Women and Journalism. London: I.B.Tauris.

10. Business of news

* Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. Forthcoming. “The Changing Economic Contexts of Journalism.” In Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Thomas Hanitzsch and Karin Wahl-Jorgensen. https://rasmuskleisnielsen.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/nielsen-the-changing-economic-contexts-of-journalism-v2.pdf.

11. Innovation in the media

* Küng, Lucy. 2015. Innovators in Digital News. RISJ Challenges. London: Tauris.

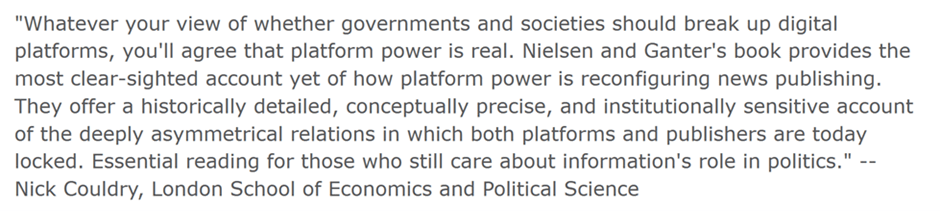

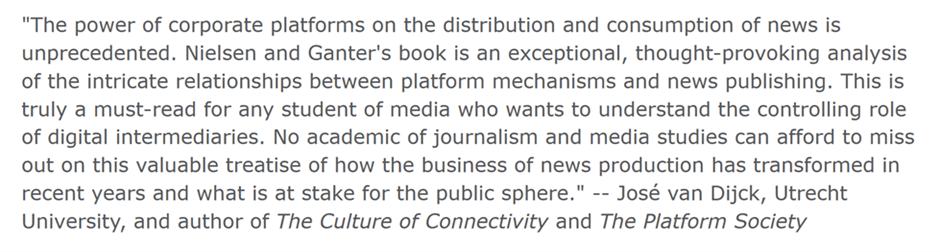

12. Platform companies and news media

* Bell, Emily J., Taylor Owen, Peter D. Brown, Codi Hauka, and Nushin Rashidian. 2017. “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism.” https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:15dv41ns27.

13. Digital media and technology

* Dijck, José van. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

14. Disinformation

* Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Report to the Council of Europe. https://shorensteincenter. org/information-disorder-framework-for-research-and-policymaking.

15. Democracy, journalism, and media

* Schudson, Michael. 2008. Why Democracies Need an Unlovable Press. Cambridge, UK: Polity. (Especially the chapter “Six or Seven Things that Journalism can do for Democracy”)

16. Censorship and propaganda

* Simon, Joel. 2014. The New Censorship : Inside the Global Battle for Media Freedom. Columbia Journalism Review Books. New York: Columbia University Press.

17. International/comparative research

* Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2005. “Comparing Media Systems.” In Mass Media and Society, edited by James Curran and Michael Gurevitch, 4th ed., 215–33. London: Hodder Arnold.

There are topics not yet on the list (local journalism, for example), and the list reflects the biases of published English language research and of our personal/professional networks in tending towards studies of and from Western countries, often specifically from the US. (It also reflects the fact that I (a) have learned a lot from my time at Columbia University and (b) am proud of the work we have done at the Reuters Institute.) The list is thus, like any list, limited, but we hope it is potentially useful and interesting, at least as a starting point, and hope journalists all over the world will find it useful.

Let us know what you think, we plan to update it going forward.